We’ve come a long way, Baby!

As we celebrate The Philadelphia Society’s 50th Anniversary, the time seemed right to update and modernize our website.

Since 1964, The Philadelphia Society has helped renew the conversation about liberty given shape in the social, economic, political and constitutional history of our communities, colonies, states, and nation.

The emergence of liberty seems to go hand-in-hand with the ability of people to communicate and debate the meaning and purpose of liberty. The story of liberty in many ways is also the story of technology and the story of whether technology becomes the master or the servant of our higher ends.

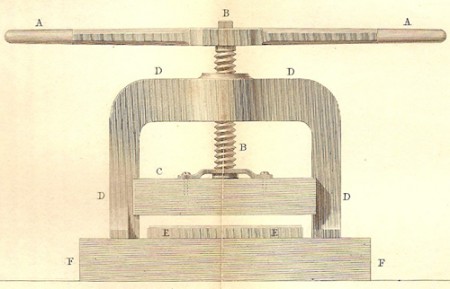

1780 James Watt copying press patent diagram

The American Founders were active letter writers, and by the time of the Constitutional Convention, Franklin, Jefferson, and Washington were already putting to use the newest communications technology of the day, the letter copying press.

By 1964, when The Philadelphia Society was founded, the “Ditto” machine was giving way to “xeroxing,” but our Society archives still contain many of the thin, delicate “carbon copies” of letters from Don Lipsett to his many correspondents, as well as telegraph receipts.

Daniel Walker Howe’s remarkable contribution to the Oxford History of the United States, covering “The Transformation of America, 1815-1845,” is titled What Hath God Wrought–hearkening back to the demonstration message Samuel Morse successfully sent by telegraph from the U. S. Supreme Court Chamber in Washington, D.C. to Alfred Vail in Baltimore.

Howe frames the history of the early 19th century as a “communications revolution”:

The invention they [Morse and Vail] had demonstrated was destined to change the world. For thousands of years messages had been limited by the speed with which messengers could travel and the distance at which eyes could see signals such as flags or smoke. Neither Alexander the Great nor Benjamin Franklin (America’s first postmaster general) two thousand years later knew anything faster than a galloping horse. Now, instant long-distance communication became a practical reality. The commercial application of Morse’s invention followed quickly. American farmers and planters–and most Americans then earned a living through agriculture–increasingly produced food and fiber for distant markets. Their merchants and bankers welcomed the chance to get news of distant prices and credit (1).

Our generation, too, has lived through another communications revolution.

Philadelphia Society members cheered, and some participated first-hand, as the fax machine and samizdat helped to open the Iron Curtain. The power of communications technology was further demonstrated in the 2013 political revolution in Egypt, fueled by protesters’ use of blogs and social media.

Bill Campbell, Secretary of the Society from 1995-2014, built the Society’s earliest website, making widely public for the first time meeting programs, audio clips, and papers of speakers. Instead of a letter copying press, however, he was assisted by the PDF, the portable document format with which anyone reading this post should be well familiar!

Philadelphia Society member George Gilder wrote in 2000 of the coming “telecosm.” “The computer age is falling,” wrote Gilder,

before the one technological force that could surpass in impact the computer’s ability to process and create information. That is communication, which is more essential to our humanity than computing is. Communication is the way we weave together a personality, a family, a business, a nation, and a world. The telecosm–the world enabled and defined by new communications technology–will make human communication universal, instantaneous, unlimited in capacity, and at the margins free (2).

At the margins. Ahh, there’s the rub. The margins are always changing. And even as the cost of communication moves to free, new problems appear. With Eliot, amid the cacophony we may ask:

Where is the Life we have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?

The cycles of heaven in twenty centuries

Brings us farther from God and nearer to the Dust.

The lot of man is ceaseless labor,

Or ceaseless idleness, which is still harder,

Or irregular labour, which is not pleasant.

And so, as we celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Philadelphia Society, we look not merely to our past but to our future. The nature of man is to quest and attain and quest anew. New desires and new horizons always rise up before us. And, as Sam Gregg recently reminds us, freedom is necessary but not sufficient.

In the voices of Frank Meyer, Milton Friedman, Russell Kirk and numerous speakers at Society meetings over the past five decades, we find both timeless wisdom and a sense of urgency. We are brought to reflect on what our freedom is for. And to understand that the time to speak for liberty is now, and that this responsibility is ours.

Technology is here, at our service, helping us enter the future with the conversations of wise men and women at our fingertips… and it’s almost free.