Campbell – The Progress of Leviathan

The Progress of Leviathan

William

F. Campbell

Secretary, The Philadelphia Society

In order to introduce the theme of

this conference I have prepared a video which rather starkly lays out the theme

of the progress of Leviathan from the Bible to Hobbes to Rousseau.

Letís orient ourselves by

starting from the present. What

does the word leviathan mean

to people today? Put simply, the

word is used by many political scientists and economists to refer to a state

which has too much power, a state swollen with growth and overly centralized.

Two authors in particular (who will be familiar to many in this Society)

have discussed the problem explicitly. The

Southern agrarian, Donald Davidson, whose name will come up in the discussion

tomorrow, published a book in 1938 entitled, The Attack on Leviathan:

Regionalism and Nationalism in the United States.

The classical liberal, Robert Higgs, published in 1987 a book

entitled, Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American

Government. These two authors

share with our Society a love of ordered liberty and a hatred of the

overweening, Leviathan state.

It is a fact, however, that most

people who use the term leviathan never stop to explain it.

Even many Hobbes scholars donít spend much time worrying about the

central image of the book.

Therefore, in this video entitled, “The Progress of

Leviathan” I have tried to capture in images and music the transformation of

the symbol of Leviathan from a negative figure of evil and sin in the Scriptures

to its more positive use in Hobbesí classic, The Leviathan, and finally

to its culmination in Rousseau and the French Revolution.

Hopefully, you have had a chance

to acquaint yourself with some of these images by examining the frontispiece of

Hobbes Leviathan and the print of Gillray which are on the tables and

easels outside.

Slide 1 is an illuminated manuscript from

theVatican Bible portraying Job, the Devil, and God.

It will set the stage for much of what you will see and hear

tonight.

First of all the music which you will be hearing on

the video is “Satanís Dance of Triumph” by Ralph Vaughn Williams.

It is a part of his larger composition, Job: A Masque for Dancing.

The context is, of course, the

Book of Job from the Old Testament. And

why should Satan dance in triumph? Satan

dances because he has been allowed to inflict untold evils upon the upright and

virtuous Job. Satanís argument to

God is that Job is only good because of his material and familial prosperity.

Indeed, it is only after everything is taken away from Job, including

much of family, possessions, and his physical health, that Job begins to

practice his proverbial “patience.” But Jobís patience is perhaps closer

to Margaret Thatcher who said on January 2, 1983: “I am extremely patient

provided I get my way in the end.”

Whatever patience Job has is not

matched by his wife who tells him to “curse God and die.”

Job does not take this advice but he does curse the day of his birth.

Here we see the first appearance of Leviathan: “Let those curse it who

curse the day, who are skilled to rouse up Leviathan.”

In Slide 2 we

see what Leviathan looks like. This

image of the great serpent is found in the Church of St. Foy in Conques, which

is in southern France. Appropriately

enough as we shall see, it is part of a larger Romanesque sculpture of The Last

Judgment.

The full-scale treatment of Leviathan is in chapter

41 of the book of Job. God taunts

Job with the puniness of his power: “Can you draw out Leviathan with a

fishhook, or press down his tongue with a cord?

Can you put a rope in his nose, or pierce his jaw with a hook?”

Chapter 41 which gives the fullest

description of the Leviathan concludes with the following words: “Upon earth

there is not his like, a creature without fear.

He beholds everything that is high; he is king over all the

sons of pride.”

Slide 3 shows what happens

in the belly of the beast. Being

king over all the sons of pride is continued in this scene where we see, a proud

knight toppling from his horse and a figure representing lust, to the right.

The Leviathan, here, is king of the proud.

For Slide 4 we move to the Cathedral of

Bourges and its Last Judgment tympanum. The

Last Judgment portals in medieval art usually portray Christ in Majesty combined

with St. Michael weighing the souls in the scales or vanquishing Satan with a

military flourish. The great

serpent, here, is the great Leviathan, and its jaws are the jaws of hell which

swallow the damned. Turmoil and

confusion swirl around these scenes.

Princes, popes, and prelates often figure in these

Last Judgment scenes. Jobís

answer to his critics in Chapter 12:21-25 prefigures this judgment of the

nations and the churches: “He [God] pours contempt on princes, and looses the

belt of the strong. He uncovers the

deeps out of darkness, and brings deep darkness to light.

He makes nations great, and he destroys them; he enlarges nations, and

leads them away.”

Slide 5 is a close-up of

the previous scene which captures the description of the Leviathan in Chapter 41

where he is portrayed as a fearsome creature with details of boiling pots,

flames coming forth from his mouth, and all the accompanying images used in the

pictorial visions of Hell.

Figures of Leviathan-like monsters

are not restricted to the Last Judgment. They

also appear in more unlikely places in medieval Christian art.

Slide

6 is the Adoration of the Magi from the Church of Ste.-Trinite in

Anzy-le-Duc.

This rather unusual sculpture shows the three wise men

presenting their gifts with trumpets blowing. Mary and Christ receive them but

Maryís foot rests securely on the Leviathan creatures beneath her.

In Slide 7 we show a

portrayal of the Harrowing of Hell in which a Leviathan-like monster is often

shown. This is a 14th

century silk from the Narbonne altar, currently in the Louvre.

It shows Christ on Holy Saturday rescuing souls, probably Adam and Eve,

from the mouth of the Leviathan. To

the right is the famous Noli me tangere with Mary Magdalene and Jesus on

Easter morning. Again the mouth of

the sea monster is symbolical of the devilís kingdom and Christ in effect has

to pry loose the vicious jaws to save the Old Testament souls.

In contrast to Job with his puny powers, Christ is often portrayed as

just the one to pierce the jaw of Leviathan with a hook.

One of the more graphic Last Judgments is Slide

8 which comes from Queen Eleanorís Apocalypse (1242-1250), now at Trinity

College, Cambridge. You definitely

wouldnít want to meet this monster in a dark alley.

Up to this point, the figure of Leviathan has been

a devil-like figure who, like Satan, embodies pride both human and angelic.

This kind of sin can only be conquered by the patience of God.

In the Old Testament and the New Testament, as we

well know, the battle against pride and ingratitude is never-ending.

The social theory that comes out of the Bible and infuses the Middle Ages

is one that emphasizes intermediary institutions.

Families, guilds, universities, the aristocracy, the churchóall are

restraints upon the centralized powers that are beginning to arise in the modern

world. But these intermediary

institutions must be constantly reformed so that they themselves do not become

worshippers of earthly power or overly desirous to dominate.

My interpretation of these developments follows the

lead of Robert Nisbet in his book, The Quest for Community, who has

traced this decline of intermediary associations from the medieval period to

Hobbes and finally to Rousseau.

The culmination of this rise of centralized power

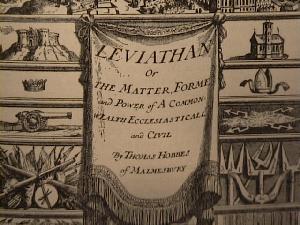

states can be seen in Slide 9 which is the title page of Hobbesí Leviathan.

The name of the book is

ensconced in emblems to left and right showing secular power on the left and

religious power on the right.

In Slide 10, we see the

body of Leviathan with sword and bishopís crozier coming out of the soil.

Although it is hard to see, it is significant that Leviathanís body is

made up of individual persons. Here,

the mystical body of Christ, which incorporated individual Christians as limbs,

is replaced by a purely human solution.

Thus the body politic takes on a new meaning.

According to Nisbet, “The modern StateÖis an inverted pyramid, its

apex resting upon the 1651 folio edition of Hobbesí Leviathan.”

(Nisbet, p. 129) Hobbes

declares that intermediate associations within the State “were many lesser

Common-wealths in the bowels of a greater.”

He compares them to “wormes in the entrayles of a naturall man.”

In essence, Hobbesí Leviathan state concentrates total authority and

power in the center.

Hobbes is hostile to all the intermediary associations which

formerly had been the stuff of politics in the Middle Ages.

Even families are reduced to voluntary contracts and agreements.

As we move to Slide 11, we

make the transition to Rousseau and the French Revolution.

Here we see the Duke of Bedford displayed as the Leviathan.

The print is James Gillrayís The New Morality;–OróThe Promisíd

Installment of the High-Priest of the Theophilanthropes, with the Homage of

Leviathan and His Suite. August 1, 1798, for the Anti-Jacobin Magazine

& Review. It was based on a

Poem by George Canning, the future Prime Minister, who in his turn based it on

Edmund Burkeís defense of his life against the attacks of the Duke of Bedford.

We see William Godwin portrayed as a donkey, Thomas Paine as a tailor,

and the Rev. David Williams as a marvelous snake.

Slide 12 shows

Larvelliere-Lepaux, one of the French leaders of the Theophilanthropes reading

from The Religion of Nature with the pillars of London Saint Paulís in

the background to journalists from the Morning Post and the Morning

Chronicle.

The final Slide 13 captures

the essence of the French Revolution and the thought of Rousseau.

Here we have the three “anti-graces” of justice, philanthropy, and

sensibility shown for what they are. Justice

is on the left with the sagging breasts and Medusa type locks.

She carries daggers in both hands, has Egalite wrapped around her waist

while her foot tramples the scales of justice.

Philanthropy squeezes the world in

a mad embrace with the Ties of Nature and love of country at her feet.

And finally Sensibility sheds big tears over a dead bird in her hand and

a copy of Rousseau by her side. Her

foot rests securely on the severed head of Louis XVI.

The unitary state has reached its theoretical apogee, and the symbol of

Leviathan has undergone its full transformation.

The horrors of totalitarianism of the Nazi and Soviet types in the 20th

century are only a more successful version of the French Revolution.

Now that you are familiar with the basic underlying types

of images, let us run the video.